It’s pretty standard for entities in multinational companies to have unique functions. One entity may be a manufacturer. Another, a distributor. Another may perform research and development. But no matter how great the disparities in what each one brings to the table, these entities often have common needs that have nothing to do with their actual purposes.

Human resources, accounting, legal services, financing, IT support. Every multinational business needs such services, and related parties often supply them for members of the group—or sometimes, the entire group. Service transactions between related parties is a well-known form of transfer pricing transactions. But while multinational companies see service transactions as ways to improve efficiency, productivity, and performance, tax authorities see service transactions as an easy way to shift profits into low- or no-tax jurisdictions. So, service transactions tend to draw a lot of unwelcome attention from tax administrations and a lot of trepidation from taxpayers.

Taxpayers aren’t wrong to feel uneasiness about service transactions. Putting a dollar value on services can be like trying to assign a dollar value to motivation. Or laughter. There’s a lot of subjectivity, which gives tax authorities a lot of leeway.

But with the right thinking and diligent documenting, service transactions don’t have to be intimidating for taxpayers. In fact, on the following pages, we’re going to discuss how service transactions can be an opportunity to make multinational companies shine.

Service Transactions and the Global Tax Landscape

For taxpayers, the goal of transfer pricing documentation is simple—you have to prove that related-party pricing meets the arm’s length standard. This is true for the transfer pricing of services, just as it is for goods. However, services can be more complicated for both taxpayers and tax administrations. For example, in recent years, many well-known companies, like American Express and General Electric, have moved back-office operations to a business-services outsourcing hub outside of New Delhi. India’s tax authorities think multinational companies are getting a bargain on these services, given location savings, like low wages. Thus, they are notorious for scrutinizing service transactions—and they are especially diligent about services involving IT.

What is an appropriate markup for intragroup services? Ultimately, that’s all the taxpayer needs to determine and support. Sounds simple enough, right? Well, in 2019, India’s tax authorities expected to see a 15%-to-25% markup on back-office services. A huge—some would say, inflated—markup.

To put this in perspective, the U.S., along with most other countries, would expect a 5%-to-7% markup for back-office services. But India feels that given the exchange in currency and location-specific advantages, companies are getting a 7%-to-8% return on their investment, whereas in the U.S., they would get a 1%-to-2% return. So, the Indian tax authorities think a 5%-to-10% markup is just not enough.

In fact, they often challenge the way taxpayers characterize their services in their functional analyses. They claim services should be classified as “knowledge process outsourcing,” which warrants higher markups than the common back-office service classification, “business processing outsourcing.”

India isn’t alone. China is notorious for scrutinizing intragroup services. Australia watches for intragroup services in low-tax jurisdictions. The Netherlands and Canada are open about scrutinizing intragroup services, along with so many other countries. In fact, taxpayers are up against constant scrutiny. Tax administrations demand outrageous markups in their local jurisdictions; challenge functional characterizations to justify markups; and at times, add location savings to the value of low-value services.

What is a taxpayer to do? Prove intragroup services are priced according to the arm’s length principle and make sure there are supporting documents to back up the needs for the service. Proving the need for service is key to proving a taxpayer isn’t using intragroup services just to shift profits to a low- or no-tax jurisdiction. And that begins with the benefits test.

The Benefits Test

Before taxpayers determine arm’s-length pricing, taxpayers have to prove that the related-party service is warranted. You won’t see this in other forms of transfer pricing—if a taxpayer is a manufacturer for Estée Lauder and produces mascara brushes and sells them to a related-party distributor, the taxpayer doesn’t have to prove it’s necessary for the business to manufacture and distribute makeup products.

But if Estée Lauder U.S. receives back-office support from a related-party hub in India, then the company has to demonstrate not only arm’s-length pricing, but also that the service is necessary. By necessary, we mean it has value for the business.

In other words, related-party services must pass the benefits test.

It may sound extreme but remember: Intragroup services aren’t fundamental to an entity’s business function. A centralized HR function doesn’t help Estée Lauder’s manufacturers to manufacturer more mascara brushes. It’s peripheral support. So, tax authorities want proof that it’s necessary. Specifically, tax authorities want proof that if an intragroup service wasn’t available through a related party, the business would seek out the service from an unrelated company.

It doesn’t take much to convince tax authorities that multinational companies are deliberately eroding tax bases in high-tax countries and shifting profits to lower-tax jurisdictions. Without this proof, tax authorities are likely to assume that multinational companies are participating in tax avoidance under the guise of service transactions.

Components of the benefits test:

- The taxpayer has to prove the economic value of the service they received.

- The taxpayer has to prove it would have been willing to enlist an independent party to provide the service, if it weren’t available in the group.

Excluded Services

Certain types of services will never pass the benefits test, because they are excluded from intercompany transactions: Shareholder activities, like admin costs for a parent company or shareholder meetings, are excluded because group entities don’t need them to do business. Services that are duplicated fail to qualify, as well. If a parent company, for example, performs the payroll function for a bunch of its subsidiaries around the world, but one subsidiary has its own payroll department, then the subsidiary doesn’t need the parent company’s service. This duplication would not qualify as an intercompany service, because the subsidiary wouldn’t be willing to pay for a service it already does.

Companies that benefit from services incidentally would also be disqualified. For example, say, your neighbor decides to renovate. Maybe he lines his walkway with gorgeous plants and hires landscapers to dress up the yard. Then he paints the exterior of his house. As a result, home prices in your neighborhood increase and suddenly your house is worth more. Well, your neighbor isn’t going to knock on your door and say, “Pay up. Here’s your portion of my painting bill.” You’ve benefitted incidentally. Lucky you.

It works the same way with companies. For example, if our parent company launches a marketing campaign that benefits a manufacturer—maybe demand grows for those Estée Lauder mascaras—but the marketing campaign wasn’t created to benefit the manufacturer directly, it’s disqualified as an intercompany service as the manufacturer would not be charged.

Excluded Services:

- Shareholder Activities

- Duplicated Services

- Incidental Benefits

Factors of Comparability

As always in transfer pricing, we know we want to align comparability between controlled and uncontrolled transactions. But what are we actually comparing when it comes to service transactions? First, we look at the type of service. Generally, legal services are benchmarked against legal services. Research and development services against research and development services and so on.

Another thing to consider is, how many adjustments are required? A taxpayer could look at a legal service and see that the hourly rate included business development expenses for one transaction, but not for another. Those rates have to be adjusted to make an apples-to-apples comparison.

Service transactions have comparability challenges. A third-party law firm may provide legal services to its client, but those contracts are not public so the conditions and pricing can be hard to determine. As with other types of transfer pricing transactions, taxpayers need to benchmark against third-party transactions. It is never okay to rely on the “going rate.”

Intragroup Service Transactions and Comparability

Once a taxpayer justifies that a service qualifies as an intragroup service, then the transfer pricing analysis can begin. As with transactions involving tangible goods and intangible property, the transfer prices for intragroup services must ultimately meet the arm’s-length standard. To prove that a service transaction is priced within arm’s-length range, a taxpayer has to evaluate how independent parties—unrelated companies—would price the same service. That’s where transfer pricing methods come in.

There are five transfer pricing methods approved by the OECD and all of them can be used for service transactions. The U.S. offers an additional method: the services cost method, which can be used to simplify analyses, but it can only be used on certain services.

To begin an economic analysis, the taxpayer has to select what the OECD refers to as “the most appropriate method,” which is known as “the best method rule” in the U.S. They have the same objective: to pick the method that is most organic to the service transaction.

How does a taxpayer select the most appropriate method? Remember, parts of transfer pricing are subjective and method selection is one of them. The most appropriate method depends on the comparability information that the taxpayer has access to: For instance, a taxpayer will want to compare an intercompany transaction to an uncontrolled transaction that works the same way. A company that sells management services to a subsidiary isn’t going to compare that to a manufacturer producing bottles for a soft-drink distributor. The pricing of the bottles has no bearing on intragroup services.

As with other types of transfer pricing transactions, a taxpayer will want to consider the quality and quantity of data and any assumptions that were made. For example, a U.S. parent may give services to subsidiaries in Poland and Romania. The taxpayer may assume that the markets are similar and may analyze the transactions under that assumption. The taxpayer also wants to examine how arm’s-length results change due to data deficiencies.

Then the taxpayer has to consider the information at hand. What are the strengths and weaknesses of each method in relation to the data? What does the functional analysis reveal about the nature of the controlled transaction? How reliable is the information about the unrelated parties?

Transfer Pricing Methods

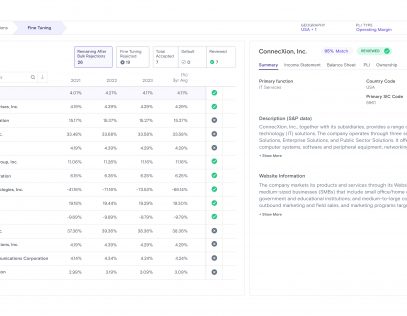

For service transactions, there are six Transfer Pricing Methods, which are shown here.

Traditional Transactional Methods:

- Comparable Uncontrolled Price Method (CUP)/Comparable Uncontrolled Services Price Method (CUSP)

- Resale Price Method (RPM)/ Gross Services Margin Method (GSMM)

- Cost-plus Method (CP)/ Cost of Services Plus Method (CSP)

Profit-based Methods:

- Profit-split method

- Transactional Net Margin Method (TNMM)/Comparable Profits Method (CPM)

Services Cost Method

- For U.S. service transactions only.

Services Cost Method

In 2007, the IRS wanted to make things easier for taxpayers. It’s true! The compliance burden for low-markup services was great for multinational companies, and certainly the IRS didn’t have resources to waste evaluating transactions that weren’t going to pay out. The services cost method (SCM) was launched. The method can be used at the taxpayer’s choosing—if the service qualifies as a low-value service.

What makes the services cost method less burdensome for taxpayers? It allows taxpayers to compare service costs without comparing profit. The catch? Only certain services qualify. To use the SCM, as it’s often called, a service must either be on the IRS’s whitelist—a list of acceptable services—or the markup for the service must be less than, or equal to, seven percent. If one of those conditions is met, a taxpayer can employ the services cost method.

If one of those conditions is met, then the service must pass the business judgment rule. This means the taxpayer must determine that the service in the intragroup transaction doesn’t contribute to an integral part of the business or give a business a competitive advantage. This is another one of transfer pricing’s subjective moments. The business judgment rule is based on a taxpayer’s reasonable judgment and the IRS can always challenge that.

What gets complicated about this rule is that the same service can qualify for one company and not for another. Let’s say, for example, a pharmaceutical business has centralized accounting services inside the group. Accounting isn’t an integral part of the pharmaceutical business. Pharmaceutical companies don’t profit from accounting, so this service could qualify for the services cost method in a pharmaceutical group. However, in a financial consulting firm that manages customer accounts, it wouldn’t qualify because the service is an integral part of the business. Another example might be data entry. At a hospital, entering data into the patient record system is not a competitive advantage, but at a data processing center, it might be. Transfer pricing always has to be seen on a case-by-case basis.

The IRS has a list of services that don’t qualify for the services cost method:

The Blacklist

- Manufacturing

- Production

- Extraction, exploration, or processing of natural resources

- Construction

- Reselling, distribution, acting as a sales or purchasing agent, acting under a commission or other similar arrangement

- Research, development, or experimentation

- Engineering or scientific

- Financial transactions, including guarantees

- Insurance or reinsurance

The Whitelist

- Payroll

- Premiums for Unemployment

- Accounts Receivable

- Accounts Payable

- General Administrative

- Public Relations

- Accounting and Auditing

- Tax

- Compliance

- Budgeting

- Treasury Activities

- Statistics

- Human Resource Services

- Computer Support

- Database Maintenance

- Legal Services

- Insurance Claims Management

- Network Administration

Keep in mind that while the services cost method may be less of a compliance burden in terms of an in-depth analysis, it still requires supporting documentation. Taxpayers have to demonstrate that the service is low value, that’s it’s not a central business activity, that it doesn’t give the company a competitive edge, and also that’s it’s not on the IRS’s blacklist. Transfer pricing studies, contracts, intercompany agreements, invoices, workpapers, SEC filings, company websites can all help to justify that a service qualifies for the services cost method.

Supporting Documentation

- Transfer Pricing Studies

- Contracts

- Intercompany Agreements

- Invoices

- Workpapers

- SEC Filings

- Company Websites

The Simplified Approach

The services cost method is an IRS method and can only be administered if a U.S. entity is selling or buying intragroup services. So, where does that leave taxpayers who are involved in intragroup service transactions outside the U.S.? The OECD has also recognized that low-value service transactions may not warrant time and resources from other tax administrations, so it recommends a simplified approach for low-value-add services. For services that meet these low-value requirements, the OECD recommends a standard profit markup of 5% on these services.

Simplified Approach Criteria

- Services must be supportive in nature

- Services are not part of the core business

- Services do not require valuable intangibles

- Services do not assume significant risk

Comparable Uncontrolled Price Method / Comparable Uncontrolled Service Price Method

Of course, not all services are low value. How do other methods work in determining arm’s-length pricing for service transactions? Much of the same way they work for other types of transfer pricing transactions.

The comparable uncontrolled price method, or CUP method under the OECD methods, is known as the comparable uncontrolled services method, or CUSP under the IRS methods. The method works the same way it does in other types of transactions: It compares the price for services provided in a controlled transaction to the price of those transferred in a comparable uncontrolled transaction.

If a taxpayer has access to reliable data from comparable uncontrolled transactions, then this method is the way to go. It simply compares the price of an intercompany service transaction to the price charged between two similar independent companies.

Tax authorities love it because it’s easy to draw conclusions about pricing through apples-to-apples comparisons. For taxpayers, however, it’s tricky because this method requires such a high level of comparability to produce reliable results. Many multinationals turn to internal CUPS when using this method—comparing what a related entity charged a related entity to what that same entity charged an unrelated company. That works well when you’re dealing with tangible goods like Estée Lauder’s mascara brushes—for what did Estée Lauder’s manufacturer sell those brushes to a related-party distributor versus an independent distributor? If the manufacturer sold to a related party for $5.00 and to the independent distributor for $5.00, you have an arm’s-length price.

However intragroup services don’t contribute to the core value of the business, so most multinational companies provide them to related parties—not external ones, so often internal CUPS don’t exist. Given the high comparability standard the CUP method requires, it isn’t often used on intragroup services.

Resale Price Method / Gross Services Margin Method (GSMM)

Taxpayers who can’t access information about strict product or service comparability, may need to look to a method that focuses more on functions and risks. The resale price method, known in the services world, as the gross services margin method, compares the gross profit margin of an intragroup service transaction to the gross profit margin in uncontrolled transactions involving similar services. The uniqueness of each service transaction, however, makes it very difficult to meet the GSMM requirements. This method is most often used for transactions involving agent services, intermediary functions, or distributors. Let’s say Estée Lauder India is a manufacturer of mascara brushes and Estée Lauder U.S. acts as a commission agent for Estée Lauder India by arranging for Estée Lauder India to make direct sales of the brushes to third-party customers in the U.S. market. Estée Lauder U.S. receives a commission fee from Estée Lauder India on the sales price of the brushes sold in the U.S. Estée Lauder U.S. also arranges for direct sales of similar brushes by unrelated foreign manufacturers—let’s say Chanel—to third-party customers in the U.S. market and charges Chanel a commission fee of 5% on the sales price. If Estée Lauder U.S. charges India a 5% commission fee on its sales price, then it can be concluded that the price was at arm’s length, as the commission fee charged in transactions involving uncontrolled manufacturers was also at 5%.

Cost Plus Method (CP) / Cost of Services Plus Method (CSPM)

The cost of services plus method compares a controlled services transaction’s gross profits against the cost of sales to that in an uncontrolled service transaction. Basically, the service provider is asking, “what is the markup I earn as the service provider?” To use this method effectively, however, the cost of the services have to be easily identified. Those costs might include salaries for marketing staff, materials and supplies consumed in rendering such services and any other costs incurred for rendering the services.

Let’s say Estée Lauder India provides design services for Estée Lauder U.S. The combined cost of services rendered is $100 combined and Estée Lauder India charges $125 for the services—a markup over the cost of 25%.

We would then look at third-party transactions where entities in India were providing design services to its customers. As long as the markup on the entire spend is 25% then we are operating at arm’s length.

Costs of sales can be accounted for in different ways, which can throw off comparability. Given that this method is based on cost, it isn’t often used for service transactions.

Profit-split Method

The profit-split method is used to divide profits between related parties. It’s often used for transactions involving intangibles when it’s hard to find reliable comparables. Tax authorities love this method because they can almost always make a case that more profits belong in local jurisdictions.

The profit-split method is rarely, if ever, used on service transactions. The method takes the profits between entities in a transaction and divides them based on each entity’s functional profile—the entity that contributes more value winds up with more profits.

While it sounds simple, the profit-split method requires more subjectivity than other methods and that can result in conflicts with tax authorities. Using this method, routine profits are easily distributed, but dividing the remaining non-routine profits carries a degree of arbitrary decision-making, which tax administrations are happy to dispute.

Given that intragroup services take place in the majority of multinational groups, reliable comparables aren’t difficult to find. Thus, the profit-split method is better reserved for transactions involving hard-to-value intangibles, where finding comparables might prove more challenging.

Comparable Profits Method (CPM) / Transactional Net Margin Method (TNMM)

The transactional net margin method is known as the comparable profits method in the U.S. It’s most commonly referred to as the TNMM and it’s a lifesaver for transfer pricing executives when reliable comparables are hard to find or costs are difficult to discern.

The TNMM compares the net margin between controlled transactions and comparable uncontrolled transactions. It’s the most commonly used transfer pricing method—employed in roughly 80% of all transfer pricing transactions, intragroup services included. The method wins taxpayers over with a relatively relaxed level of comparability and insensitivity to minor differences between comparable transactions.

So, let’s say Estée Lauder India is providing back-office services to Estée Lauder U.S. Estée Lauder India has an operating profit of $25 and total operating costs of $125. So, the net cost-plus margin is 25%. If a 25% net cost-plus margin is in the range of our comparable companies’ net cost-plus margin for similar services, then we are within arm’s-length range.

The Takeaway

For multinational companies, intragroup services may be used to maximize efficiency, minimize costs, and provide consistency throughout organizations. For tax authorities, however, service transactions are an obvious gateway to base erosion and profit shifting, and so service transactions are often scrutinized.

Given the level of surveillance, many taxpayers are intimidated by intragroup service transactions in terms of transfer pricing, because services can be hard to value. Tax authorities in different jurisdictions often see the value of service transactions through the lens of their own potential local revenue gains, which can lead to resource-draining disputes.

However, with the right know-how, conscientious economic analyses, and supporting documentation, taxpayers can easily demonstrate that intragroup services are priced appropriately and executed, not to save on taxes, but as an investment in the group’s overall business.