It began with a clear goal: to update the global tax system to better suit the digitalized marketplace—where economic value and “presence” are less defined than the physical borders governed by tax authorities.

That process, now under the auspices of the OECD’s Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project, has evolved (or devolved, depending on whom you ask) into a Gordian knot of fractious, increasingly complex technical negotiations, which may never actually yield a clear outcome.

What’s now called BEPS 2.0 has broken into two separate parts, Pillars One and Two, each of which is held together by its own jumble of changing rules, technical calculations, debates, and pressures (both internal and external). The trajectories of these two components of tax reform have proven to be quite different. For all the handwringing and arm-twisting it required, Pillar Two—aka, the Global Minimum Tax—is already enshrined into law in three dozen countries, and appears to be firmly (if not globally) on its way to adoption as a new standard. (We discuss Pillar Two in a separate white paper.)

The future of Pillar One—aimed at reallocating taxing rights from low-tax investment hubs to countries where economic value is created—appears far less assured. In this white paper, we discuss what it is, how it came to be, the significant obstacles it faces—and how companies should prepare for an outcome nobody can predict.

A Heroic Journey… or a Quixotic One?

A century ago, the global tax model was built around the physical presence of businesses, typically factories, in multiple countries. In today’s digital economy, presence is often virtual—and the old rules have proven to be no match for the IP-driven tech giants of the world. These MNEs, whose business models and operations are fluid, and whose biggest profits flow from intangible assets that “live” everywhere and nowhere, had profitably parked their crown jewels in the most tax-advantageous locations around the world, irrespective of where they actually generated those profits.

Fearing that an outdated, analog tax system was letting online income slip through the cracks, the European Commission in 2018 argued for special rules to establish the concept of “digital presence,” and to begin to impose tariffs on these digital companies. In short order, a parade of countries began unilaterally enacting digital services taxes (DSTs) aimed squarely at the (mostly American) digital behemoths they felt were evading taxes at the expense of local coffers.

The US cried foul, and vowed to fight back against any new levies that would single out its superstar tech brands.

No country likes trade disputes. No company likes to be double-taxed on its income. And nobody likes the specter of tax uncertainty. In this no-win situation, the G20 and OECD stepped into the breach,

launching the BEPS 2.0 “Inclusive Framework” to address both the challenges around digitalization of the economy and the potential impact of DSTs on international tax cooperation.

It took three years and countless tortuous negotiations, but in July, 2001, a deal was signed by 138 countries to overhaul how governments tax MNEs—a semi-official “birth certificate” for the two Pillars. Whether this giant global gambit pays off in the end will determine whether the mission was heroic or doomed. The jury may be out for a while.

A Pillar of Salt?

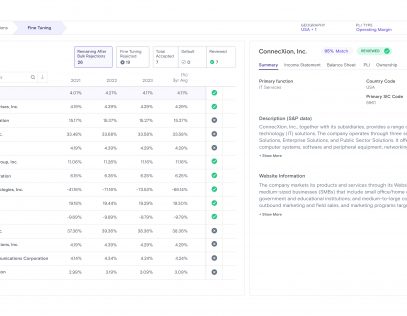

The scope of Pillar One has been substantially narrowed since its ambitious beginnings in 2018, when it would have covered 8,000 MNEs across all sectors. In its present form, its main component will affect only a small group of the world’s most profitable companies (specifically excluding those in regulated financial services or extractive industries): those with annual revenues over €20 billion and profit margins over 10%. This elite group of about 106, largely US-based companies—not all of which are actually digital companies—would then be required to reallocate 25% of their residual profits (meaning, in excess of 10% of revenue) to the actual countries where they make sales. After a seven-year “review period,” that €20 billion threshold may fall to €10 billion.

Despite its narrower scope, the financial impact of Pillar One would be undeniable: the OECD estimates that 70% of taxing rights, representing about $200 billion in profits, would shift from low-tax hubs to market jurisdictions. While it is intended to be merely a zero-sum redistribution of the corporate tax base, due to the jurisdictional tax-rate differences (which was the whole point, after all), implementation would lead to an aggregate tax increase of between $17 and $32 billion (based on 2021 data).

And what would those MNEs get in exchange? Certainty over whether or not they are “in scope” of these rules, shielded from overlapping taxation, and the biggest carrot of all: the elimination of most of the digital services taxes (DSTs) that are a thorn in the side of the household-name companies they target. All part of a concerted effort to create a coherent and equitable international tax framework that could cater to the needs of both American and non-American countries.

The US and Pillar One

Now the hard part: Unlike Pillar Two, Pillar One is a tax treaty which would need to be ratified by at least 30 jurisdictions to enter into force—including those that are home to at least 60% of in-scope MNEs.

Translation: Without the US, this isn’t going anywhere. First, any tax treaty requires a two-thirds vote in the US Senate to be ratified—and in the present political reality that would be, to put it charitably, a long shot. There is a good deal of hostility in the US Congress to the OECD’s grand plan (not just on the GOP side), despite the fact that one of its main drivers was US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen.

Second, notwithstanding their desire to get rid of the DSTs and the specter of double taxation, US companies with highly digitalized business models have expressed deep concern about the potential impact of Pillar One on innovation, competitiveness, and economic growth.

And third, the fiendishly technical aspects involved with implementing Pillar One—including the endless development of standardized rules and procedures—require so much

work and debate that they may collapse in the morass of their own complexity. Not a good look for America’s impatient, ambitious tech sector.

And it’s not as if the US had been ignoring the problem of profit shifting. While the OECD was debating BEPS, there were parallel developments happening stateside, including the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI) provisions—introduced as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017—aimed at preventing US MNEs from shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions. Unfortunately, reconciling GILTI with Pillar Two’s Global Minimum Tax was a nonstarter, primarily for internal political reasons.

Trying to conform it to Pillar One will likely face the same fate, but for a different reason: GILTI is unilateral. Given the size and power of the US economy, the worry on the other side of the pond was that GILTI could severely impact the global tax landscape, undermine the competitiveness of their own tax systems and businesses, and even influence where MNEs choose their headquarters. Another worry was the question of a potential tug of war (or double taxation): as GILTI aims to tax the foreign income of US MNEs, European countries were wary of their own taxing rights’ being superseded.

Amount A and Amount B: Not as Easy as A-B-C

Just as BEPS 2.0 had to be divided into two separate projects to have a shot at succeeding, wrestling Pillar One into a form that could be ratified by a critical mass of countries required a nuanced, paring-knife solution, rather than a meat-cleaver one.

So the OECD announced that its work will be constellated around two separate focal points, which it baptized—with its typical poetic flair—“Amount A” and “Amount B.” In the simplest terms, Amount A is about moving tax rights around: who gets the right to tax, what gets taxed, and where the tax goes. Amount B is about ensuring that routine tasks like marketing and distribution lead to a fair payment, even if traditional transfer pricing methods might not fully capture it.

It’s important to start with the easy-to-understand stuff. Because the details can be mind-boggling—and the challenges these proposed measures will likely face in the real world could make even the most starry-eyed tax idealist (if such a person even exists) hang their head in despair.

Amount A

Amount A gets the heaviest lift: figuring how to fairly distribute taxing rights for digital MNEs—recognizing, for the first time, that their value creation isn’t solely tied to physical presence, but also to factors like user participation and marketing intangibles.

To get there, negotiators must first set the rules for deciding which portion of the enterprise’s profits to reallocate, and then establish a formula for the allocation. Given the amount of moving parts and demands, those rules are, understandably, technical and extremely complex. But we could simplify them by breaking the process down into five steps: (a) determining if a multinational group is in scope, (b) identifying eligible market jurisdictions, (c) calculating Amount A profit, (d) allocating this profit to each jurisdiction, and (e) ensuring relief from double taxation.

When you get out of the weeds, deeper issues surface. Outside partners have plenty to say.

The G-24, representing developing countries, has raised concerns about Amount A’s connection to withholding taxes. They fear the consideration could undermine some of these countries’ current taxing rights and diminish the appeal and significance of Pillar One for their constituent nations.

In the US, while broadly supportive of the principle of shifting corporate taxation from places of production to places of consumption, the Tax Foundation, called the rules around Amount A a “complex mess,” arguing that it allocates “only a fraction of the profits of a fraction of taxpayers to the location of final consumption,” resulting in a “distortionary tax base that falls heavily on US taxpayers relative to foreign ones.” Considering the current political climate in the United States, concerns like these alone could spell doom for Amount A in its present form.

Amount B

Amount B’s job is simpler and more straightforward than its alphabetical cousin. It’s designed to simplify the transfer pricing of baseline marketing and wholesale distribution activities by streamlining administration, reducing compliance costs, and addressing the associated tax challenges.

Also, the updated scope of Amount B will be much broader than Amount A: it will benefit more taxpayers and reduce disputes around distribution activities, which the OECD says account for a significant portion of transfer pricing disputes in low-capacity jurisdictions. In essence, Amount B seeks to establish a standardized baseline return for activities within its scope, and offer a uniform and geographically consistent method to assess these transactions. To that end, it determines fair remuneration for routine functions, acknowledging their contribution to profitability.

Naturally, defining what constitutes “routine functions” and “fair remuneration”—and coordinating Amount B with existing transfer pricing rules—presents significant technical, industry-specific, and policy challenges. It’s a complex task that requires balancing the interests of multiple stakeholders and addressing concerns about the potential impacts on businesses, while striking a balance between simplicity and effectiveness. Little wonder that it is still bogged down in debate. While the OECD originally intended to tuck the Amount B rules into its updated 2024 Transfer Pricing Guidelines, that process, too, is in limbo at the start of this new year.

Digital Services Taxes

With the conspicuous exception of Canada, the thirty-some countries that either have enacted, or are planning to enact, DSTs as part of the deal have agreed to put them on ice through 2024—if… at least 30 countries sign the so-called Multilateral Convention treaty. Since this is (optimistically) expected to occur in 2025, that option was extended another year, according to the OECD.

Given that every stone would need to be in place for this Pillar to stand up, the stakes appear to be higher even than the likelihood of success.

How to Assemble a Plane While in Flight—So It Can Land

Hope springs eternal when it comes to international agreements. Multiply that by 1,000 when those agreements involve multilateral tax treaties.

The original plan was for the OECD to complete its work on the MLC and hold a signing ceremony by end of 2023, in the hope that it could enter into force in 2025. Yet, at this writing, intense negotiations have yet to yield a votable draft. Considering the heft of the latest draft (issued in October 2023), which runs over 1,000 pages—not to mention the cold winds blowing out of the Capitol Building—that prediction may be very optimistic.

But what if, as seems quite likely, this doesn’t happen on schedule—or ever? We could see an outcome nobody wants: an unraveling of the whole Pillar One project, even as Pillar Two has just taken off on its shaky maiden flight. A return to retaliatory trade actions, double-taxation, tax uncertainty—and those digital services taxes—is possible. A messy prospect, with the United States once again in the spotlight.

In the face of this kind of uncertainty, what should MNE tax departments do?

The right place to focus right now should be on the OECD’s rulemaking: will they—can they—be improved? What might Pillar One look like multilaterally if the US opts out: total chaos and trade wars, or some kind of third way or workaround? The discussions that are happening right now at the OECD on Pillar One are changing the way that tax administrations are thinking about transfer pricing. MNEs need to be following along and thinking about that, too.

When you consider how hard it is to get countries, cultures, and corporations to cooperate on any ambitious and unprecedented mission, you have to ask: could this process—the work of 140 nations, the G8, the G20, the OECD, and countless finance ministers for more than a decade—have gone any differently? To some, even getting this far is nothing short of a miracle. And long-term missions often have the hidden benefit of momentum.

Even if most don’t hold out hope that Pillar One in its final form will see the light of day, can anyone afford to bet the company on that certainty? The odds may be small, but they’re not zero: so best to be prepared for the turbulence ahead.