What is an uncertain tax position and how do you account for them under U.S. GAAP?

With governments around the world scrambling for tax revenues, the subject of uncertain tax positions has been thrust into the spotlight. In the ordinary course of business, the average corporate tax return will include several tax positions. A tax position merely reflects how tax law is interpreted and applied to your company’s circumstances. The tax position could qualify for a tax deduction or credit, or even whether your company is subject to tax in a certain jurisdiction. Since tax legislation, case law, and tax authority practice do not always provide clarity on all transactions, uncertainty sometimes exists as to the income and deferred tax treatment of certain positions, which are open to interpretation. These findings emphasize uncertain tax position assessments.

“Asking corporations to identify their UTPs is intended to cut the time that the IRS requires to review returns. That can help both the agency and taxpayers.”

Even if you’ve never had to worry about reporting uncertain tax positions (UTPs) on your company’s tax return before, you could have to report them in the future. Starting with the 2014 tax year, corporations that have assets of at least $10 million and meet other filing requirements—such as filing audited financial statements or including UTPs in others’ audited statements—must file Schedule UTP (Form 1120), “Uncertain Tax Position Statement.” That’s a shift, as the UTP reporting rules were limited to companies with assets of at least $50 million for the 2012 and 2013 tax years. The expanding scope of UTP reporting is significant. According to some tax experts, filing this schedule may increase the chance that your company will be audited.

Due to the complex nature of the calculation of a tax position, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) has issued specific guidance on how to account for uncertainty in taxes in financial statements. It prescribes a two-step process, in which the recognition of the effects of a tax position should be considered first and thereafter its measurement.

Recognition of Effects of Uncertain Tax Positions

Entities should recognize the effects of an uncertain tax position when they believe that it is “more-likely-than-not” that the revenue authorities will, upon examination, sustain their tax position. “More likely than not” means that there is, in management’s opinion, a likelihood of more than 50 percent.

When making this assessment, management should:

– Assume that the tax position will be examined by the revenue services and that they will have full knowledge of all circumstances. This means that an entity cannot account for an uncertain tax position because they believe the risk of an audit or detection is low.

– Calculate the effects of the tax position based on legislation, rulings, case law, and the administrative practices of the revenue authorities in so far as they as widely understood.

– Consider each tax position on its own, without offsetting it against other uncertain tax positions.

Only when a tax position meets this recognition threshold should it be measured to determine the amount to be recognized in the financial statements.

Measurement of Effects of Uncertain Tax Positions

When an uncertain tax position has met the recognition criteria, the amount to be recognized should be calculated by using the cumulative probability approach, which means that the effects of the uncertain tax position should be measured at the amount for which the cumulative probability is higher than 50%. This process involves:

- Determining a range of outcomes and assigning a probability to each. This is a matter of judgment and will depend on factors such as the nature of the tax position and the weight of the legislation in the entity’s favor, the degree to which the entity is prepared to defend the position, the likely amount for which it will be open to a settlement, and the expected attitude of the tax authorities.

- If any single outcome has a higher than 50% probability, the effects will be recognized for that amount.

- If no single outcome has a higher than 50% probability, the effects will be measured for the highest amount at which the cumulative probability exceeds 50%.

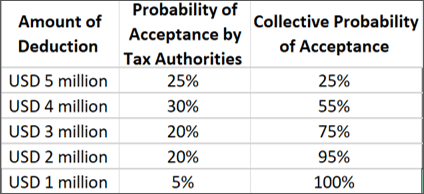

Let’s look at an example to understand this calculation:

XYZ Smith, Inc. is a subsidiary of ABC Co. XYZ claimed a tax deduction of $5 million on its tax return and in its financial statements related to head office royalty charges allocated to them by ABC. It is probable that, if challenged, the tax authorities will ultimately give XYZ a deduction for these charges. However, the amount of the deduction is uncertain, although the likelihood that the deduction will ever be questioned by tax authorities is nominal. XYZ Inc, uses U.S. GAAP and its income tax rate is 21%. XYZ considers the amounts and probabilities (if challenged) of the possible estimated outcomes as follows:

The measurement of such tax-return positions is based on the largest benefit that is greater than 50% likely of being realized. Since $4 million is the largest amount of benefit that is greater than 50% likely of being realized upon ultimate settlement, XYZ should recognize a tax benefit of $840,000 (USD 4 million x 21%) in its U.S. GAAP financial statements.

What entry should XYZ, Inc. make to record this uncertain tax position?

Assuming a tax benefit of $1.05 million ($5 million x 21%) was already recorded in the financial statements, a liability $210,000 ($1 million x 21%) should be recorded representing the difference between the benefit measured under ASC 740 of $840,000 and the tax benefit claimed on the income tax return of $1.05million.

The journal entry would be:

Dr. Current income tax expense (income statement) $210,000

Cr. Income taxes payable (balance sheet) $210,000

The following examples illustrate types of uncertain tax positions:

- Whether or not to include income in an entity’s taxable income.

- Uncertainty as to the deductibility of an amount for tax purposes.

- Uncertainty whether the tax authority and the courts will accept a certain transfer pricing methodology.

- Uncertainty created regarding the correct interpretation of the tax law as a result of a new tax court case.

- Different interpretation of legislation between the tax authority and the taxpayer/tax advisors; and

- Different interpretation of a double taxation agreement between the relevant tax authority and the taxpayer/tax advisors, for example, whether an amount is subject to withholding taxes or not.

Managing Uncertain Tax Positions

The assessment of an uncertain tax position is a continuous process. All unresolved UTPs must be reviewed at each balance sheet date. Any changes must be based on new information like tax law changes, new regulations issued by taxing authorities, and interactions with the taxing authorities. Changes in UTPs should be recognized in the period the facts change. Disclosure is required in this situation if the amounts are material. Eventually, unrecognized tax benefits can be realized when the underlying tax position is effectively settled, or the statute of limitations expires. When this occurs, typically the UTP liability is debited, and income tax expense is credited.

The emergence of new reporting consideration for uncertain tax positions is a continuous process, which does not end with the initial determination of a positions’ sustainability. Management must continuously determine whether the factors underlying the sustainability assertion have changed and whether the amount of the recognized tax benefit is still appropriate. To constantly manage and track the UTP data source and calculations, most organizations rely on spreadsheets to support these critical reporting processes. One of the leading issues that most organizations contend with while using spreadsheets and manually collecting the data is that the process becomes super time-consuming. Not to mention the spreadsheets being black boxes that are difficult to control and are prone to errors.

The good news for tax departments is that there are growing number of purpose-built software solutions/technologies available to replace spreadsheets and improve the tracking of the tax positions and reporting process. Most companies will find that implementing a software tool will not only streamline the process but also see reduced points of risk and chance for errors. The technology within the tool supports with keeping an organized inventory of all the positions, calculating tax and interest for each tax position and report them with a full audit trail while still allowing to make the decisions on what to disclose effectively and accurately to the IRS and other auditors.