Transfer pricing regulations are tighter than ever. Documentation requirements demand endless reporting and mountains of data. Couple that with the fact that tax transparency efforts are as much as about disclosures to investors and the public as they are to tax administrations. And while well-meaning taxpayers may try to diligently calculate arms-length ranges, we are all operating with a major vulnerability: Subjectivity.

The Role of Subjectivity in Transfer Pricing Benchmarking

Arm’s-length pricing depends almost entirely on your transfer pricing benchmarking selection. Historically, that has required personal judgment from tax professionals. What I deem relevant may be different than what you deem relevant as both quantitative and qualitative criteria are used to include or reject potential comparable companies. That’s what makes benchmarking the most challenging aspect of performing a transfer pricing analysis.

But in the age of information, automation, and intelligent technology, should personal subjectivity still have a place in transfer pricing benchmarking? Having seen the countless benefits of tax technology firsthand—and knowing full well that technology has become an essential tool for tax authorities all over the world—I’d argue that it’s time for a transfer pricing benchmarking revolution.

Comparable Companies in Transfer Pricing Benchmarking: Fact or Fiction?

Transfer pricing is a unique practice. Unlike other financial analyses, transfer pricing benchmarks rely on functional comparability rather than surface-level similarities. This means companies cannot be selected solely on industry codes or financial data. For benchmarking to be accurate, taxpayers and regulators must look deeper into operational functions, assets, and risks.

The Challenge of Functional Comparability

Functional comparability requires economists to make subjective judgments about which companies belong in a comparable set The OECD has recognized that benchmark selection relies on too few data points to determine an indisputable arm’s length range. As such, over the years, the OECD, along with many policy-making bodies, have published papers about how to improve benchmarking, with the ultimate goal to reduce subjectivity and relieve the burden, financial and otherwise, of establishing a reliable comparable set.

Yet, despite these efforts, transfer pricing practitioners have traditionally maintained that perfect third-party companies that are comparable across all comparability dimensions do not exist. So, they continue to operate on the premise that subjectivity is a necessary evil in the benchmarking process.

Limiting the Options in Transfer Pricing Benchmarking

The traditional approach to comparable searches has been to identify comparable companies through a systematic approach, which limits subjectivity.

According to the Platform for Collaboration on Tax (PCT) and generally accepted transfer pricing practices, the minimum requirement for the application of the arm’s-length principle rests on two factors:

- A third-party comparable company must have available financial data.

- A controlled entity is not useful in evaluating arm’s-length profitability.

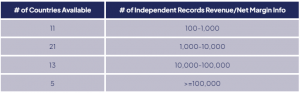

But that skeletal criterion is compounded by the unique requirements established by tax authorities surrounding benchmarks. Some forbid companies in loss positions. Others reject start-up companies. And by now, the majority of countries demand local comps, making the search for perfect comparables that much more difficult and the pool of acceptable comparables much smaller. The following table shows the number of countries and the number of companies with at least a pool of financial data in select Standard & Poor’s and Dun & Bradstreet databases:

Comparable Company Data by Country – Transfer Pricing Analysis

Using a conservative approach, 50 countries have more than 100 companies that are potentially useful in a transfer pricing analysis. If a jurisdiction has at least 100 independent companies with sufficient financial data, the next step would be to stratify those companies across functions for transfer pricing purposes.

Beyond Industry Codes: Finding More Reliable Comparables

To do so, practitioners have historically relied on industrial classification codes on industry codes found in classification systems, like the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) system, or the European equivalent, the Nomenclature des Activités Économiques dans la Communauté Européenne (NACE)—none of which were designed with transfer pricing in mind. Transfer pricing professionals used them because they were the best option available—not because they were best option. In fact, they present limitations in preparing comparable searches.

In fact, Joint Transfer Pricing Forum members in the paper JTPF/009/2016/EN, state:

“Industry codes (like SIC or NACE) do not often allow for a reliable selection of companies in the same industry. It is recommendable to concentrate more on a comprehensive selection and combination of precise keywords rather than a narrow selection of industry codes when defining search strategies.”

JTPF members also note that industry classification codes, themselves, are subjective and inconsistent, as functionally comparable companies may not be classified under the same industry code across different countries. A comparable company may be overlooked in one country and deemed perfect in another, simply because of the code under which it was classified.

PCT Guidance on Industry Codes and Benchmarking

“While typical screening processes rely on factors such as industry classification codes as a practical means of refining a search, the extent to which such a code or other screening criterion is aligned with the economically relevant characteristics of the accurately delineated transaction needs to be considered. – Profit Comparables Toolkit (PCT)”

In practice this means that just because two companies share an industry classification code doesn’t necessarily mean they’re truly comparable for transfer pricing purposes.

Classification codes are subjective themselves, as companies can choose their own industry-classification codes. Given evolving business models, many companies do not fit nicely into one specific classification.

Practically speaking, classification codes are necessary to reduce the number of companies that require more qualitative evaluation for functional comparability. However, if the classification system aligned functions across an industry, or was even representative of today’s business models, transfer pricing practitioners would not have to be as discerning about the selection of companies across the numerous comparability requirements, as outlined by the OECD.

What Makes a Company Comparable in Transfer Pricing?

The evaluation of companies for benchmarking purposes, per OECD guidance, is highly dependent on the quality of the information available.

Unfortunately, even a change in the stratification of data does not change the level of detail available. Thus, practitioners and policy-making bodies, such as the JTPF, challenge the OECD on the feasibility of meeting comparability standards, claiming they are “illusory.”

Practically speaking, the minimum criteria for identifying good benchmarks include:

- Availability of financial data

- Independence

- Overcoming barriers to entry

- Functional comparability

The Subjectivity of Functional Comparability

Of the four minimum criteria, the evaluation of functional comparability is the most subjective filter. Transfer pricing searches have historically involved reading the business descriptions of each potentially comparable company for functional comparability.

“Dr. Ednaldo Silva, founder of RoyaltyStat, now owned by Exactera, once spoke about empirical evidence that supports consistent arm’s length ranges for distributors across different industries.”

At the time, many professionals disregarded this perspective because it challenged the value that transfer pricing professionals brought to the table—the ability to identify functionally good comparables in the same industry.

But soon accounting firms began to relegate the mundane task of reviewing comparability to junior analysts or establish offices in low-cost jurisdictions, while other companies tried to create “off the shelf” benchmarks since the reliance on the industrial classification codes continued to be unreliable.

Combined with the inherent subjectivity introduced in the search process, comparables have become a major subject of debate between taxpayers and tax authorities. Given the hawkish level of scrutiny that taxpayers are under today, subjective comparables are simply no longer an option.

“Subjective comparables are simply no longer an option.”

— Key takeaway from this section

AI and Tax Technology: The Future of Transfer Pricing Benchmarking

Historically, time, money, and manpower were limiting factors in identifying comparables.

Now, finding satisfactory third-party comparable companies with objectivity is not only possible—it’s happening. Artificial intelligence (AI) is changing how we approach transfer pricing benchmarking.

AI-powered technology can evaluate companies through a transfer pricing lens, as opposed to a business lens. It can identify the most reliable, functionally comparable companies, regardless of the classification-code construct.

Comparability searches of the past required so many resources that we settled for the identification of five-to-10 broadly comparable companies.

New technology can identify more comparable companies, reduce subjectivity, and create more meaningful statistical samples, helping taxpayers stand up to modern-day scrutiny.

Why Bigger Sample Sizes Improve Benchmarking Accuracy

An increased number of comparable companies, without the subjective constraints of the classification-code construct, helps to create more statistically significant ranges that are less sensitive to individual company challenges.

It also eliminates some of the errors that are introduced through subjective screening on multiple levels of the analysis.

The use of an interquartile range is not meaningful without an appropriate sample size. Our approach to the interquartile range as a statistical approach is best supported in an example presented the PCT toolkit:

Our ability to identify more comparables based on functional comparability through a more objective process is better suited to the application of statistical approaches identified by the various policy-making bodies and economists.

Interestingly, JTPF members suggested in their report that the final outcome of a qualitatively reviewed benchmark should be in line with a “rough data dump within the database” and “big deviations” may lead to “doubts as to the reliability of the benchmark.”

In fact, the report goes on to state that too many rejected comparables should be evaluated more closely and the process of manual screening is referred to as “cherry picking.”

With new tax technology, taxpayers can avoid the accusation that they hand-selected comparables because advanced software has identified functionally comparable companies objectively, going well beyond those antiquated and subjective classification systems.

This shift toward objective, data-driven benchmarking ensures credibility with both regulators and tax authorities.

How AI Strengthens Benchmarking and Audit Readiness

Today’s tax technology can produce a much larger set, which should (with the exception of database limitations) produce all the companies that tax authorities would determine as functionally comparable. If tax authorities are going to challenge comparables, then the burden of proof is on them.

Exactera anticipates that comparable searches that continue to be prepared using traditional approaches will become easy to challenge under audit, as more third-party comparables are identified outside of typical classification codes.

Technology facilitates a more robust way of reviewing millions of potentially comparable companies that meet the minimum comparability requirements. It can streamline data gathering, eliminate manual errors, and create efficiency. And where benchmarking is concerned, it can bring transfer pricing into the modern world. “Isn’t it time to bring transfer pricing benchmarking into the modern era with Exactera?”